Challenges of Modern Agriculture: Building Resilient Food Systems in a Changing Climate

By Nicole Doll

To many, Saskatchewan is represented by what is seen in the southern half of the province: fields of crops peacefully moving in the breeze. It is a terrain that many identify as quintessentially Saskatchewan: a province that provides food for the rest of the country, and for nations around the globe. We are proudly home to some of the most productive land in the world, and to the breadbasket of Canada.

While agriculture is often considered to be the economic lifeblood of the prairies – integral to the economy and the well-being of many communities – it has not come to be that way without an environmental or social cost.

The new age of agriculture often leaves farmers with little choice but to go big or go home. Unless fields are massive, expensive equipment is available, and the operation is large-scale, it becomes much more difficult to succeed as a farmer. And while food production is so important for obvious reasons, it is the increased scale of operation that has taken a toll on the land – creating a system that works against the environment rather than with it.

The shift to large-scale agriculture is relatively recent, born out of both the industrial revolution and the post-war years when technological advances enabled machinery to replace human and animal labour, allowing for the persistence of a highly efficient system that focused on prioritizing production and profit over people and the environment.

A short history of industrial agriculture

In the early 1900s, farming was a much more prevalent vocation than it is today. A higher proportion of the population were farmers, producing a greater variety of crops, using different techniques, and heavily incorporating animal husbandry. Although some methods used during this period degraded the soil – such as intensive tillage – the small-scale farms were more conducive to creating a diversified system, which benefited the surrounding ecosystems, flora, and fauna. While these types of small-scale farms still exist, the vast majority of food produced today is influenced by the profit-driven and highly commercialized industrial agriculture system.

The more diverse, smaller-scale type of farming changed during the onset of the Green Revolution during the 1950s – 1960s. The Green Revolution significantly changed farming operations and was marked by technological advances, high-yielding varieties of seeds, and the rampant use of chemical fertilizers. Some argue that over the brief span of the 20th century, agriculture changed more than it had when it was first adopted 13,000 years ago.

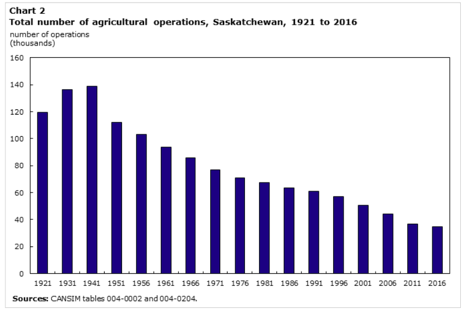

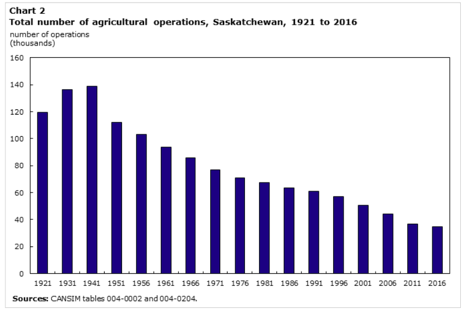

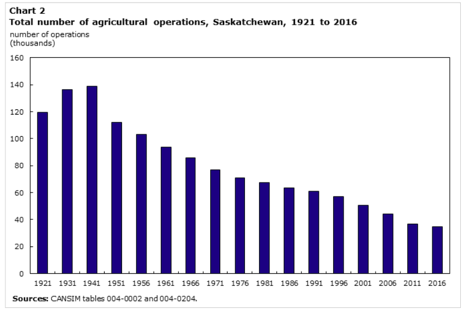

The Green Revolution forever changed agriculture in many parts of the world by creating a highly efficient system that resulted in considerably more productive crops. It created circumstances that made it more beneficial to have fewer farmers with bigger fields and large equipment. In the year 1936, Saskatchewan had about 142,000 farms. Fast forward to 2006, the number had shrunk to around 44,000. Today, the number of farmers in the country continues to shrink.

The standing impact of industrial agriculture

As the number of farmers has diminished, so has the diversity of crops and the range of tasks that are involved in production. Specializing in one or two crops became key to creating the most efficient system, giving way to genetically uniform monocultures, void of biodiversity.

Crop homogeneity further increased as high-yielding varieties were produced, giving farmers fewer options on what kind of plant species to grow. Large fields of monoculture crops resulted in a lack of biodiversity, causing fields to become much more susceptible to diseases and pests.

In a diversified system, insects and animals can dampen the effects of weeds and pests, keeping the ecosystem ‘in check.’ However, in the 12 years between 1964 and 1976, fertilizer application in the U.S doubled and pesticide usage increased by 143%.

This had significant repercussions on the surrounding ecosystem, as insects dramatically declined as well as the species that ate them. The plight of bees which is linked to the intense use of chemicals is well-known and is a worrisome problem considering that bees are responsible for pollinating much of the global food supply. Additionally, all of the excess chemicals wash away with the soil into nearby water bodies causing eutrophication, which is characterized by excessive algae growth that depletes oxygen in water bodies, ultimately leading to the die-off of aquatic species.

This highly efficient, large-scale operation of agriculture has allowed a massive increase in food production and has made for an extremely profitable system. However, the land has suffered as a result. Monocultures and chemical inputs threaten the longevity of the soil, depleting it of nutrients and diminishing fertility levels. Areas that grow food today may not be able to provide for future generations if such practices continue. The transformation to large-scale farms has also heavily increased the dependence on fossil fuels, with big machinery travelling longer distances. Combined together, these practices make agriculture responsible for 24% of the fossil fuel emissions in Saskatchewan.

Although food production has increased on a significant scale, the shift to this system wasn’t entirely based on producing more food, as there are alternative, less damaging options to increase productivity. Systematic incentives and the power of various agrochemical companies have historically favoured monocultures and factory farms, making it difficult for farmers to choose how they grow food and raise animals.

Furthermore, fertilizers and seed sectors are owned by only a few companies, giving growers hardly any options when it comes to buying product. The increase in concentration and ownership of the market can be observed in almost all sectors of the food and agriculture industry – meaning the top firms control larger shares of the market, allowing them to have influence over government policies. This has limited the choices available to both consumers and producers.

Hendrickson and James (2005) argue that consolidation directly restricts the choices and types of decisions available to farmers, forcing them to make choices that they would not otherwise make. Consolidated markets and the increased corporate power over the food system have a direct environmental impact and it affects how farmers can manage their land. Many are left in ethical dilemmas, feeling pressure from large processing and retail firms to adopt environmentally degrading practices or otherwise succumb to financial instability.

Despite the systems in place that favour the intensified practice of industrial agriculture, many growers have started their own initiatives to work with the land instead of working against it. Many examples can be seen here in Saskatchewan, which we’ll explore below.

Improving systems in place: Regenerative and Sustainable agriculture

With climate change presenting itself as an ominous, ever-increasing threat to our daily lives, global food and water security pose a growing challenge. While there is currently no consensus on just how exactly climate change will affect agriculture, many have already realized that practices will have to adapt in response to more severe weather events – droughts, floods, pests – all while trying to sustain soil health for future generations.

In realizing that we need to look for ways to combat climate change – many have turned to agriculture as a solution rather than another problem. In other words, using agriculture as a carbon sink rather than creating conditions that cause it to be a carbon source. This has led to the adoption of regenerative agriculture, which is a system of farming that uses a variety of methods to actively restore the soil, biodiversity, water quality, and surrounding ecosystems – while growing food at the same time. Moving one step beyond sustainability, regenerative agriculture actively works to improve the conditions that currently exist in a way that works in collaboration with nature – a practice that Indigenous peoples have been already doing for millennia.

Soil is a big focus here, as techniques are used to promote and improve soil quality and soil health. With healthier soil, the earth’s capacity to sequester carbon significantly improves – and thus, acts as a tool to combat climate change.

Various practices are used to achieve these outcomes, such as conservation tillage (allowing the build-up of crop residue on the soil to reduce erosion by wind and water), rotation and cover crops (planting crops for the purpose of bringing nutrients back into the soil), and diversifying crops themselves. As these practices bring life back into the soil and surrounding ecosystem, the soil becomes more resilient and thus can better withstand the severe weather events that come with climate change. Furthermore, the soil is less likely to run-off and erode with wind and water, increasing the health of nearby water bodies.

Not only does regenerative agriculture revitalize the soil and sequester carbon, but it aims to also rejuvenate the surrounding ecosystem by focusing on a diversity of crops and relying upon natural methods of pest control (such as birds and insects) rather than depending on the heavy use of chemicals.

Natural climate solutions (conserving, restoring, and improving the management of lands that increase carbon storage across forests, wetlands, grasslands, and agricultural lands) will be an integral part of dealing with the climate crisis. Studies have shown that effectively managing the land can provide one-third of the cost-effective climate mitigation needed to stabilize our climate. Carbon sequestration will be a huge part of this, but changing the way land is managed will also improve soil productivity, sustain clean air and water, and support biodiversity. Many Saskatchewan farmers are participating in innovative climate solutions through their farming practices.

Saskatchewan farmers leading the way in sustainable solutions

The ‘dust bowl’ years during the 1930s were a scary time for many farmers. Intensive tillage practices left a loose layer of topsoil that was rapidly carried away by wind and water, turning the sky black with soil at times. At the mercy of the weather, this prolonged drought exposed the shortcomings of intense tillage practices. Researchers at the University of Saskatchewan quickly started to develop different techniques that would keep soil anchored on the ground with the ability to retain moisture. However, even with new techniques, the threat of future droughts loomed.

During these periods of drought conditions, the side-effects of intensive farming practices were made clear by significant soil erosion, decreases in soil fertility, and moisture loss. With a changing climate and the increased likelihood of extreme weather events, The Saskatchewan Soil Conservation Association (SSCA) was formed in 1987 by a group of producers who saw the need to increase public awareness of soil conservation and to promote production systems that improve the health of the land for future generations.

A major focus of the SSCA is to use agriculture to mitigate climate change through the adoption of sustainable practices. Conservation tillage, for example, avoids disturbing the topsoil when farmers seed and produce crops. As a result, soil erosion is reduced, soil moisture is retained, and carbon is actually sequestered rather than released. With carbon being sequestered and stored underground, conservation tillage poses an important solution to the climate crisis.

Other sustainable practices that have been introduced include crop rotation, intercropping (planting more than one crop in the same field), and the use of cover crops. All these methods aim to improve soil health. Better soil health increases nutrient cycling, movement of air and water through the soil, and microbial diversity. With more nutrients and better capacity to store water, the soil becomes more resilient to severe weather events such as droughts.

Being at the mercy of hot, dry weather and chance weather events, data shows that Saskatchewan farmers have shifted in the favour of more sustainable practices over the past 25 years. As a result, an increased number of Saskatchewan farmers are sequestering carbon within their soils. The adoption of these practices has benefitted both farmers and the environment by sequestering carbon and maintaining more resilient soil.

These farmers are setting world-leading examples on how to promote food security while at the same time mitigating climate change by managing their fields as a carbon sink. Instead of producing food in an unsustainable manner that is harmful to the environment, they are using agriculture as a key part of the solution to fight the climate crisis. They have exemplified how agriculture and sustainability can co-exist with one another, which will be key to food security in the long term given our unstable climate.

The endangered prairie

To many, southern Saskatchewan is known as the prairies: landscapes of rippling fields that stretch for miles under a dancing sky. While many are proud to be from such a unique place, the term ‘prairie’ is often mistakenly used to describe cultivated landscapes – wheat, canola, barley, and flax among the few. Fields of crops are no doubt beautiful and evoke a sense of peace, but referring to these landscapes as prairie is a common fallacy that often waters down the significance of grassland ecosystems.

While native grassland used to make up a substantial portion of Saskatchewan, it is estimated that only 14% remain in the province. In fact, temperate grasslands are the most endangered biome on our planet. Numerous species that can only be found in prairie regions in southern Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba are now imperiled with some on the brink of extinction – species like the greater sage-grouse, black-tailed prairie dog, the burrowing owl, the swift fox, and the plains bison – just to name a few.

Before the onset of colonization, Indigenous communities stewarded the grasslands, both living off the land and managing it in a way that allowed the ecosystem to thrive. As colonizers arrived, bison – an important mega-fauna integral to the health of the prairies – were decimated. It is argued that beyond the financial benefits of bison, the mass systemic harvesting of bison was also used as a tool of oppression against Indigenous people. In the absence of the ecological management of land by Indigenous peoples coupled with the decimation of bison, the functionality of the ecosystem forever changed.

The grasslands were further degraded as settlers moved into the area in search of land that could easily be converted into crops. Land conversion, combined with oil and gas exploration, and the spread of invasive species has reduced the wide expanse of the grasslands to small, isolated patches. With only 14% of native prairie left in the province, there is a growing consensus that significant conservation is needed to protect what remains. The flora and fauna species that can thrive only in these areas depend on it. While the prairies may come off as an unassuming landscape, one quarter-section of native prairie can contain over 100 species of plants, which is critical habitat for dozens of migratory bird species.

Since much of the remaining native grasslands are under private ownership, a unique opportunity has presented itself to landowners to heavily contribute to the conservation and stewardship of this endangered landscape. Many Saskatchewan ranchers who own large tracts of property in the grasslands have brought this opportunity to fruition by managing their land to support cattle while at the same time enhancing the health of the natural ecosystem.

Sustainable growers in Saskatchewan: Ranchers as grassland conservationists

The late 1870s drew in a wave of immigrants with the promise of cheap land and a fresh start, and with this came the widespread expansion of agriculture throughout the prairies. Ranchers were also settling into the area and utilizing the natural grasslands as feed for cattle. Because ranchers were able to productively use the land in its natural state, land that would have otherwise been cultivated was conserved. Much of the large swaths of grasslands that exist in Saskatchewan today can be attributed to ranchers.

In addition to safeguarding the prairies from other forms of use, ranchers also brought back functionality to the ecosystem by re-introducing a key element that had been taken away – grazers. As mentioned above, the grassland ecosystem was kept alive by the presence of bison moving through the land – feeding, stomping, and digesting.

Historically, bison provided large-scale disturbance to the grasslands which maintained and enhanced proper ecological functioning. The large-scale disturbance caused by herds of bison that travelled hundreds of kilometers wide completely revitalized the ecosystem. The herds were so significant that they rumbled the earth as they came through, giving the loud sounds they created the nickname “Thunder of the plains”.

They strengthened the root system of the grass, churned up the soil with their hooves, and naturally fertilized the ground by urinating and defecating. This disturbance brought nutrients and life back to the soil, attracting birds and insects alike. Improved soil quality and plant health ensure that carbon dioxide is being stored underground, within the soil and plant roots, acting naturally as a climate change buffer. When grasslands are left in their natural state – in the absence of tilling and cultivation – they act as powerful carbon storages.

As grazers help build organic matter and soil health, they also help safeguard the environment from extreme weather events like floods and droughts. Healthier soil with more organic matter from grazers and plants with stronger root systems can retain and absorb more water as compared to a field that has been cultivated.

Cattle mimic bison’s role in the ecosystem

By mimicking bison’s grazing pattern and with proper care and management by Canadian ranchers, cattle can actually help revitalize the land. As cattle graze, they too allow the ecosystem to be more productive by promoting root growth and fertilizing the soil. Their presence attracts all kinds of insects, which naturally bring in birds and other insect-eating species into the area. Instead of the land becoming converted into monocultures, it remains in its natural state which supports endangered grassland species, while still providing food to Canadians.

Many ranchers are also part of programs that protect and monitor endangered species on their properties, including the program Operation Burrowing Owl, where over 350 landowners work together to conserve important grassland habitat and monitor owl populations on their land while continuing regular land-use practices.

Naturally, grazing animals are part of the grassland ecosystem. They fertilize the soil, promote root stimulation, improve soil quality and organic matter which provides flood and drought control while also providing habitat to other grassland species. When managed carefully, they are integral to the health of the landscape.

While agriculture and food production can wreak havoc on our ecosystems and contribute heavily to our greenhouse gas emissions, producers all over the world, including many here in Saskatchewan, have shown that food production can in fact be part of the solution.

By using innovative techniques and reincorporating diversity back onto the land, the soil can slowly heal over time and build up organic matter, which will ultimately help sequester carbon from the atmosphere. With healthy soil, not only will future generations be able to depend on growing food in the areas that we are today, but they will also be more resilient to extreme weather events, which are likely to become more frequent in the coming decades.

As many producers have shown, it is possible to restore the link between agriculture and sustainability. Managing the land with care will be a very powerful tool as we urgently look for solutions to fight climate change.

If you are a producer in Saskatchewan and are looking for more sustainable and resilient methods, explore this video.